PART I

I wanted to write down a version of a warm-up that I use in different ways for the events I design and run. I invite you to go through the instructions yourself as you read. Take as much time for each instruction as you feel like. Approach it with a curious slowness and a sense that there is nothing to achieve by doing this, there is merely being and observing. I will also go through the steps as I write them down. Perhaps this is a place where we can meet, even though we are separated by space and time.

First, notice your breath. If it helps to take a purposefully deeper breath, that’s great. Invite the breath to reach all the way down into the bottom of your pelvis. Let in an awareness of the circulation of breath through your body, how the breath mixes with blood flow and how the blood is related to the fluidity of your body in general. As you breathe into your pelvis, notice how it rests upon whatever is supporting you underneath. Or perhaps you are standing or lying down as you read this, in which case you should notice whatever surface supports your weight. Notice the weight itself, how it might shift from one side of your body to the other, or from front to back. Notice how it moves or changes simply by noticing it! Notice what effect this has on your muscles, your sense of your bones, notice the weight’s relation to blood flow and the breath. All just noticing: there is nothing to change or correct in what is happening.

Again notice the surface that you are being supported by. And take your time in noticing whatever else is around you. Get a sense of your body in the round, in a full 360 degrees, the front, sides, and back of the body. How do you take in information around you, through seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, tasting? Spend a bit of time with each sense: use your breath and take pauses to absorb the information you are gathering. The how informs the what: the kind of information you can pick up depends on which sensory aspect you focus on. And as much as each sense has its own specialized range, there is a great deal of overlap between them and how they weave together to form our perception.

Touch whatever is around you, noticing as you do that these things also touch you. Touching something with your hand is different from touching it with your head, or elbow, or foot, so try out touching things with different body parts. Notice the information touch brings forth: temperature, texture, weight, density. You can apply different pressures when you touch, light or heavy. Touch with different speeds. Touch with your eyes closed versus open. There may be a vibration created as you touch. Touch gathers a sense of proximity, and touching almost always creates sound: try listening to your hand as you move it through the air. The sound of touch also coordinates with information about texture, density, and the composition of material. You can touch as a way to produce different types of sound: rubbing produces a very different sound on the same surface as tapping and the same type of touch makes very different sounds on different surfaces or materials. You can either hold something up close to your nose or bring your nose close to something: we have a sense of proximity through smell, and however close something is changes how much we can smell of it. Then we bring in the chemical, molecular information of whatever it is we are smelling. This is a powerful way we internalize the external, very physically and literally. Whatever is in the air, we inhale into our bodies (a powerful multi-pronged filtration system in place before this air reaches the lungs, as long as it is not overtaxed): the olfactory sensors register what they can. We bring in air through the mouth as well, and we can invite an exploration of taste by trying to taste the air. I have to admit, this is hard for me, so I resort to noticing the texture, the temperature of the air and it’s movement in my mouth: thus it provides the same information as touch. Things do indeed touch our tongues as we taste them and this is a component of taste. Go ahead and taste something near you, even if it’s not edible: notice how smell and taste and touch are interwoven. Sound can be found there too, produced by licking, chewing, or sipping.

Breathe and pause. Notice the weight of your body again, being supported by the surface under it. Notice how you might feel differently than you did when we started. Take note of all that you have noticed in this short exercise. This is actually a lot of information. This was quite a touch-based exploration, and there still could be more to explore, including adding more focus on sight. You might feel fine, you might even feel refreshed. You might feel a little overwhelmed. There is a lot of information here, but do you feel that this is information overload? How does that form of fatigue feel to you, anyways? What kind of information feels excessive, and when does it feel like too much?

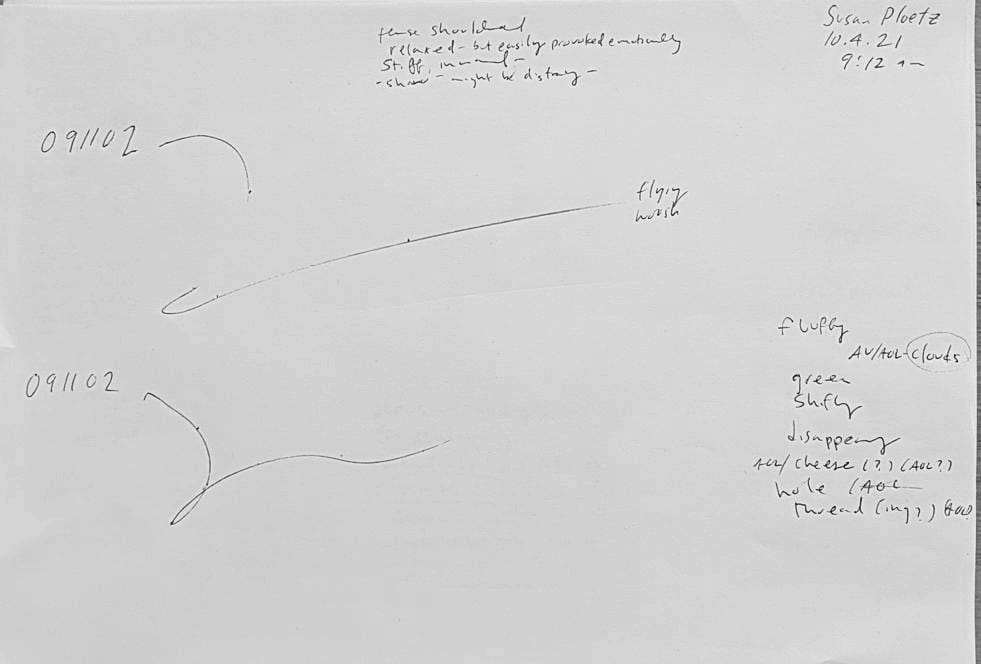

Courtesy of the artist

PART II

When we notice or take in the sensory information of the surroundings, things, and materials around us, we take in their qualities, their characteristics. The table has a texture: it’s smooth, but in some places there is a roughness or a bumpiness. There is perhaps dust or debris elsewhere, too: which is both a texture, in a way, but then also another, discrete material. We take in this information about qualities or characteristics non-verbally. In my LARPs Skinship and Sasanel, I ask participants to try to label these qualities as they feel and sense what is around them. We use this sensory input to then build magic rituals, objects and poems, or to search for intelligences or special powers: these qualities are a material’s power: the sensory information and exploration reveals what a material is capable of, what a material is.

The word quality comes from qualitas or “qualis” which is a Latinized version of the Greek word poiotēs. The general meaning is “of what kind, of such a kind” and it is formed from the same stem of interrogative pronouns and question words like qui, quo, qua, quis; who, what, why in English; wie, was, wer in German. Poiotēs (supposedly first coined by Plato) means “what-ness” or “such-ness”: in a certain way, when we sense a thing’s qualities we are sensing its suchness. Of course, what we sense or perceive is subjective, depending on our particular history with the material, or our specific physiology: a person born blind has a different (not deficient) perceptive skillset than one born with sight, and a dog, for example, has a different perceptual range than a human. In this way we met the suchness of a thing with our own suchness. It’s an encounter, and it’s relational.

This may seem a bit simplistic: OK, so the table is smooth, it feels/sounds dense, so what. However, something is happening when you slow down and notice the qualities of a material or a thing: you are building a relationship with it. The language for sensuous qualities can be quite layered. Many adjectives seem to stand on their own, like brittle or fragrant. Many adjectives (especially in English) are associative or comparative: chalky, dusty. They evoke other materials in addition to the material you are trying to describe. Many descriptive words have onomatopoeic properties: sticky, scratchy, smooth. These words sound like the sound these materials make either on their own or by you interacting with them. There is a physiological relationship and response both to the material and to the word describing it. As you sense and find ways to describe or label things, memories come up of other times in the past when you have interacted with this material, or of other similar materials or objects. Then, memories of people, events, places you associate with these qualities, materials or objects may also be evoked. There is an individual memory and a collective memory. There are quite a lot of feelings in all of this as well, and the boundary between physiological feeling and emotional feeling is sometimes thin and hard to define.

PART III

There are both magic systems and healing systems that utilize the quality of what is around us to work their supposed effects. There is sympathetic magic or “like produces like”, and Ficino says that “the way magic works is to bring things together through their inherent similarity.” There is homeopathy with its similar logic of “like cures like”. Much of conventional medicine treatments in the West follow an allopathic approach: treat a symptom with its opposite. In Chinese medicine or Ayurveda, a similar use of opposites is used but in the pursuit of holistic balance: if you are cold, for example, then drink something warm. Eastern healing practices have a very complex system of observing specific qualities and using them to heal conditions. In some somatic practices (for example ideokinesis, VMI, BMC, or somatic experiencing) we focus on the qualities that we can sense to open up our perception or (in a similar vein to sympathetic magic) we invoke the image or sensation of a quality or thing to replicate it in ourselves or our movements, and to invite new possibilities, such as inviting a sense of movement or softness into a place of holding. Sometimes focusing on qualities helps things shift almost magically: when I focus on exploring the surface that supports me from underneath, I usually release the tension in my pelvis automatically, without having to directly focus on “releasing” it. When I focus on the qualities of the bodily tissue of someone I am touching when doing a hands-on session, lymph nodes and tissue and organs can sometimes start moving and shifting without me or the other person doing anything at all besides noticing and feeling.

Some Ayurvedic healers say that anything in the world can potentially be a medicine, because everything in the world has a quality. My somatics teacher Patricia Bardi once told us that when it comes to the body, there is only information. Not that serious illness or injury isn’t real, but a type of cure comes in the form of shifting our relationship to pain and disease. If we perceive a strain or pain somewhere, we can notice the softness that might be around it or in another part of the body. By focusing on the material qualities of our bodies, we come to know it better and what it is capable of. There is a healing to be had not just in finding similarities or opposites either internally or externally, but in the space we enter in the finding itself. When we explore ourselves and our surroundings in this way, we discover time and time again: suchness.

Somatic experiencing contains the concept and role of the compassionate witness. The somatic-experiencing practitioner seeks to be the compassionate witness to the person who comes seeking treatment: guiding the seeker through sensations, pendulating in and out of difficult feelings and feelings of ease, building up to release and finding calm. The body needs this compassionate witness, this guide and protector, to find its way through itself. Perhaps this is because we all came into this world enshrined in another person: our formation came from a material attachment to another being. As much as we need this external witnessing to heal, we need to actively witness ourselves as well, and therein arise different intersecting feedback loops: witnessing our self, being witnessed, witnessing each other witnessing. This process is not limited to our the relations we form with other humans. We can approach everything that surrounds us in this role of the compassionate witness: by focusing on the qualities of everything around us and our sensory perceptions (with its wealth of physical, physiological, emotional, and mental information). We can bear witness and relate to the suchness.

Susan Ploetz (US/DE) is an artist-researcher working with somatics, theory, writing, performance, simulation, and live-action role-play (LARPing) in different configurations. Her work deals with the overlapping spaces between soma and technos; she uses imagination, magical materiality, and protocol to induce emancipatory emotive dissonances and perceptual expansion. She explores body-centered game design and narrative-building play as co-creative world-making that develops individual agency within spontaneous, ephemeral, decentralized communities.

She has presented work at such institutions as the Berliner Festspiele, Oude Kerk, Sophiensaele, ABC Art Fair, Rupert (Vilnius), Documenta 13, Portland Institute of Contemporary Art, Aoyama Gakuin University (Tokyo), and Performa. She has been a guest artist/teacher, lectured or given workshops at Universität der Kunst Berlin, Gerrit Reitveld Academie, Piet Zwart Institute, the DAAD, the Pervasive Media Studio (Bristol), SUNY Buffalo, and the Dutch Art Institute.